Seeking Quality? Start with Profitability

Quality companies grow when they make investments and expand profits. Other companies get in trouble when they make unprofitable investments. The whole idea behind investing in stocks (equity) is to grow. Fixed income is generally considered suitable for stable income; hence the name “fixed.” Long-run stock investing, by contrast, requires survival and profitable growth.

Even though profitability alone does not guarantee the “best” investment in each year, focusing on high profitability is a good start because such companies are more likely to grow and create value, especially as funding costs rise.

The Profitability-Value Nexus

We are not saying that all profitable companies are good stocks to buy. In most situations, the market is aware of a company’s level of profitability, and these stocks tend to carry higher valuations. It is possible to overpay for a profitable company, which is why valuation also matters. This is why Washington Crossing spends much time asking ourselves whether a price makes sense.

When we value a business, a vital part of the process is estimating how long a company can maintain a high level of profitability. More than this is needed for a firm to create value. Not only must a firm generate a positive return on investments, but the return must also exceed the cost of funding those investments. If, for example, a business pays 5% for capital to make an investment in a factory which, in turn, generates a 10% return, that factory creates value. On the other hand, if a business pays 10% for capital and invests at 5%, then that investment destroys value. The higher the return on capital, relative to the cost of money, the faster the company will grow and the higher the company’s odds of survival. Where companies tend to earn profits above their cost of capital, we also tend to find sustainable competitive advantages. These advantages can often last longer than many realize and be underestimated by those who focus too much on short-term results.

Rare Finds

Occasionally, we find companies that generate returns on capital above their cost of capital, but these are rare. According to a recent article and analysis by NYU Professor Aswath Damodaran, only about 30% of firms globally tend to generate such excess profitability. More often, profitable companies come under attack from competitors. When competition ensues, selling prices are pressured, and costs can rise. Profits become squeezed, and the entire value-creation process is threatened. While the companies can survive, they tend to grow slowly, pay more for capital, and have a greater risk of failure.

We prefer to pay more for profitable companies because we place a high value on having a competitive advantage in a world where such an advantage is hard to come by. This advantage can also grow when interest rates and the cost of equity capital rise, like now. In such a world, those few companies with profitable assets tend to have the wind at their back, while those without such good assets tend to fight the wind. Low or marginally profitable companies can end up on the rocks quickly when ill winds blow. This is a risk we strive to avoid at all costs.

Excess Profitability and Quality

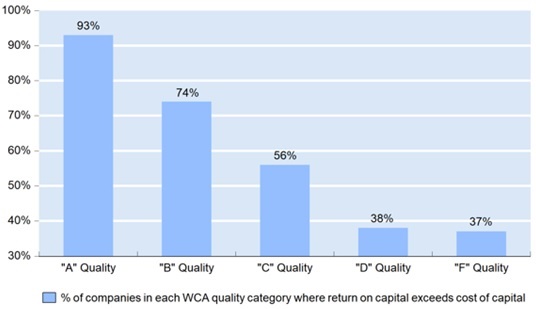

To show how the concept of excess profitability breaks down by quality, we offer Chart A, below. The chart shows by WCA Fundamental Quality Grade category the percent of companies earning a return on capital above their cost of capital. To do this, we compared the return on capital to the cost of capital for each group based on Bloomberg data for the past year. The quality grade categories divide the largest U.S. domiciled companies into equal buckets based on fundamentals. Companies deemed more durable, flexible, and predictable earn higher grades than less stable, flexible, and predictable fundamentals.

Chart A – Return on Capital Exceeding Cost of Capital, Percentage of Companies by WCA Quality Grade

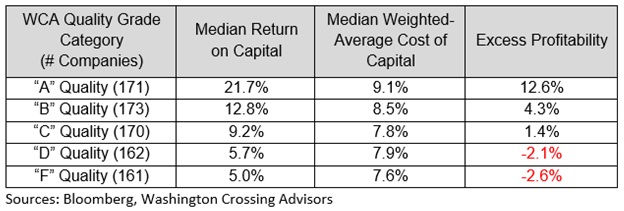

The chart above shows a far higher percentage of high-quality companies out earned their cost of capital than did low-quality companies. But how much higher was the return on capital than its cost? To see that, we provide Table A below. This table shows median measures of profitability, cost of capital, and excess return over cost of capital by quality grade category. A similar pattern emerges.

The cost of capital declines as quality deteriorates, which can seem counterintuitive. Lower-quality companies generally lean heavily on debt financing. Debt is less costly because it is tax-advantaged, because of its contractual nature, and because it ranks above equity owner’s claims in the event of reorganization or bankruptcy. As the financing mix shifts more to debt over equity, the cost of capital declines.

Table A – Profitability Measures by WCA Quality Grade, WCA Universe of Large U.S. Domiciled Public Companies

Conclusion

It is evident that while profitability alone does not always guarantee a good investment, it is an excellent place to start. We should focus on profitability in our search for quality for two main reasons. First, firms with excess profitability are far more likely to grow and survive. But most importantly, highly profitable companies are far better positioned to create value, especially if funding costs rise further from here.

So, while lower quality, lower profitability companies sometimes offer compelling discounts or high dividend yields versus high-quality, this is a style of investing we tend to avoid. We avoid low-quality, low-profitability firms because the negative surprises and downside risks of investing in such stocks usually far outweigh potential rewards, especially in bad markets when safety really matters. By contrast, higher-quality businesses with competitive moats, reasonable valuation, and excess profitability offer the opposite.