Can Policymakers Create Just

a Little Inflation?

In our last commentary, we pointed to the ongoing slide in

net new credit creation by households (the largest component

of the private sector in the United States) as a historic

event that signaled a dramatic change in the country's

financial inner workings. This raises two important

questions. First, can government spending spur a sustainable

recovery in the absence of private sector borrowing and

spending? Second, will the Federal Reserve and the U.S.

government be able to stimulate risk-taking as households,

corporations, and investors seek to reduce leverage? The

answer to these two questions will largely determine what

kind of year 2009 turns out to be.

To date, we have seen that markets have responded with tepid

enthusiasm to what now amounts to over $8 trillion of rescue

and stopgap measures taken by the Fed and the Treasury to

shore up the financial system.

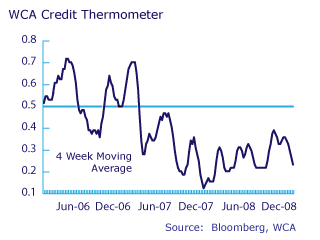

Our “Credit Thermometer”, seen below, which measures a

collection of credit indicators, has shown modest

improvement, but more than half of the index’s components

continue to show contraction. Some credit spreads,

such as the spreads that affect inter-bank lending, have

stopped widening, and have narrowed. Other spreads, such as

those found in the mortgage market, continue to widen

despite new efforts by the Fed and the Treasury to intervene

in those markets. Thus, it is not clear that the efforts of

central bankers and governments have been completely

successful in driving the market outcomes they desire. It is

also not clear what the long-run effects of market

interventions will be. Therefore, in the face of contracting

private sector demand for goods, services, and credit, we

remain skeptical that the policymakers will be able to

simply create the desired amount of modest inflation and

economic growth they seek on command.

In modern times, inflation has been the primary concern of

government and central bankers. The corrosive effects of a

rapidly rising price level were a destabilizing and painful

process during the 1970s. Price controls, automatic wage

adjustments in employment contracts, and multiple oil shocks

rapidly destroyed the ability of the economy to supply goods

and services, and impaired the purchasing power of dollars.

Today, we are confronted with the opposite dilemma of

falling prices and supply gluts. In recent months, we have

seen an across-the-board collapse in prices. Asset prices

have dropped, consumer goods prices have dropped, and input

prices have dropped. Inventories of unsold homes,

commodities, and automobiles have all risen sharply. The

bond market now is pricing in a 0.1% long-run inflation

expectation compared to a 2.5% inflation expectation just

last summer. The institute of supply management’s index of

input prices has fallen by the largest amount since just

after the end of World War II. At the same time, household

equity has fallen by $7.1 trillion, the largest

year-over-year drop on record, according to Federal Reserve

data. In turn, this has prompted a massive shift in behavior

as U.S. households have rapidly transitioned from net

borrowing to net savings for the first time since the 1930s,

based on Federal Reserve data.

Such a reversal in spending and savings patterns poses a

problem for government and bankers. Historically, they have

relied on the steady expansion of private sector credit and

borrowing as the primary spigot for money creation. This

process has served central bankers and the overall economy

exceptionally well for most of the past seventy years, as

monetary expansion and modest inflation prompted consumers

to spend rather than hoard cash and prompted risk-taking

investors to borrow and invest rather than hold cash in

unproductive, but safe investments. Now that households hold

roughly $1.40 in debt for a dollar in income, rather than

$0.40 in debt for a dollar of income as was the case after

World War II, households appear to be more concerned with

increasing their rate of savings from disposable income. We

believe that until debt-to-income and debt-to-asset ratios

stabilize at lower levels, it will be likely that the

savings rate will continue to rise and that households will

act as a drain rather than a source of net new money and

credit creation. These ratios can be improved by a

combination of debt retirement, income gains, or asset price

appreciation. Current trends have not supported job creation

or asset price inflation. Instead, the onus has been placed

on increased savings and debt retirement to make up for lost

wealth related to declining home equity and financial market

losses. These trends are particularly evident among “baby

boomers” who are moving closer to retirement and whose

funding requirements for savings are now higher, and

consumer spending needs are more moderate in the wake of the

housing bust. Without U.S. households acting as willing

borrowers, our trade partners and our policymakers will

attempt to use the U.S. government as a "borrower of last

resort" to act as counterparty to the central banks’ role of

"lender of last resort."

A higher rate of savings is something that we have seen

before. As recently as the early 1990s, the savings rate was

closer to 10% than the 0% seen in recent years. With roughly

$10 trillion in disposable income in the United States, a

return to a 10% savings rate would mean that roughly $1

trillion would, on the margin, not be available for spending

and consumption. In addition, households have eliminated,

from peak levels, $1.4 trillion of annualized net borrowing

seen in 2006. Thus the potential shift from borrowing and

spending to savings could amount to a $2.4 trillion shift.

This shift is not what the global economy has in mind and is

part of the reason why this downturn could be deeper and

longer than past cycles and why there has been a coordinated

slowdown in the global economy.

To combat this, a combination of monetary and fiscal

stimulus is being formulated. To date, we do not have a

precise understanding of the fiscal stimulus. We have a

better understanding of the monetary framework, however. The

Federal Reserve has aggressively and quickly lowered the Fed

Funds rate to effectively 0%. Such a low rate should provide

a disincentive for savings and encourage more borrowing –

precisely the opposite direction the public is leaning given

their new desire to save and pay down debt. In the past, low

yields at the bank (such as the Federal Reserve’s

maintenance of a 1% rate for overnight money following the

2001-2002 recession and terrorist attacks) created the

necessary incentives for increased borrowing and leverage

that, in turn, created rising asset and consumer prices.

Thus, the return to near 0% short-term rates, along with

other untested policy actions, undoubtedly hopes to create a

replay past easy-money cycles as a way to enliven the

expansion of credit, expand the money supply, and drive

higher the overall price level as a way of preventing a

deflation-driven policy trap.

In November 2002, for example, Ben Bernanke discussed

alternative policy options that could be used in a

deflationary environment once the Fed Funds rate reached 0%.

The

speech was given in Washington, DC before the National

Economists Club. During the speech, Dr. Bernanke downplayed

the likelihood of deflation in the United States, suggested

that it is easier to avoid deflation in the first place

rather than to fight it once it begins, and defended the

idea that, under a paper money system, government can always

generate a positive rate of inflation. He also outlined six

alternative policy actions that the Fed, in conjunction with

cooperative efforts from other parts of government, could

turn to once the Fed Funds rate reached the "zero-bound." In

no particular order, the list includes:

1)

Commitments to holding the overnight rate at zero

"…One approach, similar to

an action taken in the past couple of years by the Bank of

Japan, would be for the Fed to commit to holding the

overnight rate at zero for some specified period."

~ Bernanke (November 2002:

“Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here”)

2)

Ceilings for yields

"…A more direct method,

which I personally prefer, would be for the Fed to begin

announcing explicit ceilings for yields on longer-maturity

Treasury debt (say, bonds maturing within the next two

years)."

~ Bernanke (November 2002:

“Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here”)

3) Agency

debt

"…Yet another option would

be for the Fed to use its existing authority to operate in

the markets for agency debt (for example, mortgage-backed

securities issued by Ginnie Mae, the Government National

Mortgage Association)."

~ Bernanke (November 2002:

“Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here”)

4) Yields

on privately issued securities

"…If lowering yields on

longer-dated Treasury securities proved insufficient to

restart spending, however, the Fed might next consider

attempting to influence directly the yields on privately

issued securities."

~ Bernanke (November 2002:

“Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here”)

5)

Exchange rate policy

"…Exchange rate policy has

been an effective weapon against deflation. The Fed has the

authority to buy foreign government debt as well as domestic

government debt. Fed purchases of the liabilities of foreign

governments have the potential to affect the market...for

foreign exchange. Although a policy of intervening to

affect the exchange value of the dollar is nowhere on the

horizon today, it's worth noting that there have been times

when exchange rate policy has been an effective weapon

against deflation."

~ Bernanke (November 2002:

“Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here”)

6) Direct

open-market operations in private assets

"…If the Treasury issued

debt to purchase private assets and the Fed then purchased

an equal amount of Treasury debt with newly created money,

the whole operation would be the economic equivalent of

direct open-market operations in private assets."

~ Bernanke (November 2002:

“Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here”)

We can clearly see how these

policy ideas discussed in 2002 are making their way into

current policy decisions. The December 16 Federal Open

Market Committee statement that accompanied their decision

to reduce the Fed Funds’ target rate to a range of 0 - ¼%

included language that specifically mentions many of the

alternative policy actions outlined in Dr. Bernanke’s 2002

deflation speech. In the statement, the FOMC mentions that

they will support financial markets through open market

operations and other measures that sustain the size of the

Fed’s balance sheet at a high level. The Fed is also

expanding its balance sheet by purchasing a large quantity

of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities to provide

support for the mortgage and housing markets. Plans have

been floated which envision reducing the rate on conforming

30-year mortgages to as low as 4.5%. According to the

statement, the Fed is also evaluating the potential benefits

of purchasing longer-term Treasury securities. These

actions, along with recently created loan facilities, allow

the Fed to inject capital into the financial and banking

system by expanding the size of its own balance sheet

through the issuance of newly issued Treasury debt and the

simultaneous purchase of these non-Treasury assets.

It should be noted that the

Bank of Japan also bought asset-backed securities, equities,

and extended the terms of commercial paper operations.

Despite Japan’s efforts, they were unsuccessful in reversing

the deflationary tendencies in their economy. Some have

argued that they acted too late and, hence, the rapid

response by policymakers over the past year by the Fed and

the Treasury. So far, market response has been tepid as

evidenced by generally down-trending stock prices, elevated

high credit spreads, and the ongoing slide in real estate

values. The tepid-but-positive market response to last

year’s actions suggests that doubts remain as to their

long-run effectiveness but also demonstrates that swift

action may have prevented even greater deterioration.

To further paraphrase Mr.

Bernanke's speech, these kinds of actions are untested, and

it is impossible to "calibrate" the economic effects of such

nonstandard means of injecting money. Of particular concern

is the Chairman's suggestion that Japan was unable to thwart

growing deflationary problems because of the size of the bad

loans that were never properly purged from their banking

system. These bad loans, coupled with the inability of Japan

to come together politically on a course of action for

reform, helped produce a calcified financial system and

undermined BOJ efforts to stimulate growth through monetary

policy. In response to why the Japanese experience was not

transferable to the United States, Dr. Bernanke stated that

"the U.S. economy does not have Japan's massive financial

problems." It is unclear whether or not the ongoing

financial sector write-downs, which have recently topped $1

trillion, along with ongoing loan impairments, places the

U.S. financial system in a condition similar to that of the

Japanese or not. In our view, the proof will lie in the

volume of loan creation that follows.

With the household sector

retreating from the use of borrowed funds to make purchases,

and the re-emergence of a drive to higher savings and

lessened risk appetites, we believe that policymakers will

face an uphill struggle to create growth and inflation. Ben

Bernanke, however, seems to believe that "policymakers

should always be able to generate increased nominal spending

and inflation, even when the short-term nominal interest

rate is at zero." We are skeptical, especially given the

fragile condition of our financial system, rising distress

among borrowers, and ongoing declines in collateral values

in the form of real estate and stock portfolios. To again

use Dr. Bernanke's words, a "well capitalized banking system

and smoothly functioning capital markets are an important

line of defense against deflationary shocks." Since the

banking system is tied to housing as collateral for its

loans, we believe that until we see housing prices

stabilize, this important "line of defense" will remain

under assault and be potentially ineffective in transmitting

the desired monetary policy stimulus.

In 2009, we believe $500

billion to $1 trillion of new money should be created to

offset rising private sector losses and increased savings

requirements, and to offset a similar amount of financial

sector asset losses in order to maintain upward pressure on

prices. Without robust private sector lending, the obvious

alternative way to inject money into circulation is through

direct Federal Government spending. Such spending used to be

called “pump priming” and had the aim of propping up demand

and employment until private sector businesses again ramped

up spending and hiring plans. As the Federal Government

embarks on massive spending in 2009, we wonder if such

spending will actually spark the creation of sustained

expansion or whether it will produce illusive or uneven

results. If the stimulus is only focused on demand creation,

without adequately incentivizing entrepreneurial risk-taking

in the private sector, it is hard to envision a sustained

expansion taking root from the effort. If, on the other

hand, more comprehensive legislation emerges that improves

the landscape for entrepreneurial risk-taking, such efforts

would likely have a more positive effect, because they will

prompt the kind of autonomous investment spending and, with

it, produce the kind of multiplier effects in the economy

that lead to sustainable job and income growth.

In the meantime, we remain

skeptical of the ability of policymakers to offset the drive

by households to bolster savings at the expense of current

consumption and the need for financial intermediaries to

curtail leverage and bolster capital positions in

anticipation of fresh losses. 2009 will likely bring a

rising tide of unemployment, bankruptcies, and compressed

profits. We recognize that stock and credit markets will

sniff out opportunity before the actual turn in the economy,

but given the size of the distortions in the years leading

up to this crisis, coupled with our skepticism over the

ability of policymakers to engineer desired outcomes at

will, we remain cautious at this time with a heavier

emphasis on cash and bonds over stocks.

|

Past Commentaries

December 11, 2008

Household Credit Turns Negative...

More

November 21, 2008

Credit: Don't Want It... Can't Get It...

More

September 24, 2008

Downgrading Outlook Based on Credit Freeze

More

September 15, 2008

Equity Markets Stumble on Lehman, Merrill, and AIG

More

September 9, 2008

No Change In Strategy On GSE Action

More

July 31, 2008

Quick Take on GDP Report

More

July 21, 2008

Valuation Are Better, But Markets Are Not Out of the

Woods

More

May 20, 2008

Buy the Dips

More

March 10, 2008

Investing During Recession

More

January 22, 2008

Global Sell-off

More

December 27, 2007

Outlook 2008

More

December 7, 2007

NBER President Raises Recession Concerns

More

November 28, 2007

Equity Risk Heightened - Allocation Remains Defensive

More

September 25, 2007

After the Rate Cut

More

July 30, 2007

The Case For Growth

More

June 15, 2007

Data Affirms Tactical Asset Allocation Posture

More

March 19, 2007

Cutting Earnings And Equity Target

More

| |